Figure XXI

July 24, 2006

And dappled light and dark with leaves, and momentary glimpses of the sun through cloud, Nancy bends back bracken from the path, folds away the mossy arm of a pear tree hung with grey and swollen fruit. And as if forgotten, there it sits, as if to say “civilisation has crumbled and I am all that’s left” it bows beneath the tangled canopy, humble, rusting. Its windows are blurred with a veil of green. One of its headlamps has fallen through. Bindweed has torn the bumper to the ground to be swallowed up by dank and light-starved weeds.

And is this all there is? Is this all she brought her out to see?

“It was Henry’s father’s,” Nancy says, clearing nettles to reveal the number-plate but finding that the thing had long since fallen off, “he was in the diplomatic service. Do you drive?”

“I don’t think it’s going to go, Nancy.”

“No, but I mean, can you? I thought I’d sell it, but it rather needs bringing out of all this mess.”

Anita stands disheartened. She watches as Nancy clears branches from around the driver’s door, but the door will not open. Is this what little hope was offered? It is as if she cannot see it, cannot see what a mess the car has become in the years since her husband died. She tells Anita what a good car it was, and Anita listens silently to the stories of trips down to Brighton, picnics on the Downs.

In the air there is the sound of scaffolding being erected some streets away, and overhead the rumble of a passing aeroplane, but here in the garden there is only this; the snap and snare of twigs being broken away from a rusty car.

“What are you doing?” Anita finally asks, “Why are you doing this?”

Nancy continues with her weeding, pulling coils of bramble from beneath the car’s mudguard.

“It’s too late,” Anita says, “there’s more plant than car here.”

“People buy cars like this even as wrecks.” She stops, leaning her arm on the bonnet. “It’s all there is left.”

What Nancy means by this, Anita does not comprehend. It is probably money, but if so the sale of this car will not save anything. Though they live in the same house, they know virtually nothing about each other’s lives, but the one thing they do know, the thing that they can see in each other is their suffering. They recognise it in each other’s looks and movements. Anita cannot deny her hope, even if the act seems ridiculous, its basis is that of change; it is rectifying something so small, but it is something. It is a remedy of sorts.

She gets to her knees and begins to prize a root away from the axel. For the moment, she thinks, this is enough.

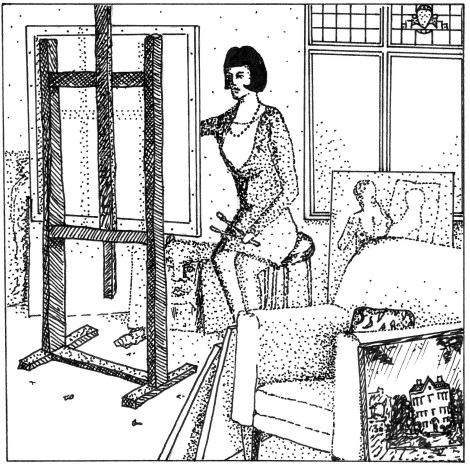

Figure XVIII

July 19, 2006

She finds her in the hallway, holding her coat like an unfolded child.

“Anita?” the ampibrach quivering in the air between them, not caught, not taken, “are you going out?”

She stirs, as if noticing Nancy for the first time, “I’m not sure, I don’t know any more.”

Such connections falter for the moment. Either one of them might smile, or simply turn and the day would progress along its intended course, but here the hesitation is what is felt. Their mutual doubt, uncertain but in being so, somehow concrete. It is seen by both of them in this instant. Neither moves, neither speaks and it is as if this shared commotion of unbeing seems to stretch before them with all its lunatic possibilities, out of the hallway, out through the stained glass doorway and into the gunmetal sky beyond.

“I think I’ve felt like that for years.” Nancy says finally, “Undone. Not knowing. Maybe it’s what happens.”

“I got a letter,” says Anita, putting down her coat, “they won’t be exhibiting my paintings.”

No condolence is given, but neither of them seeks it. Theirs is a matter of fact; a statement of the hopelessness of failing.

“So no plans for the day then?” Nancy ventures.

“No. Not today, not tomorrow.”

“Horrible isn’t it?”

“I don’t know why I do it. I don’t even enjoy painting very much.”

“I think too often it’s easiest to stick with what you know.”

“Even if you hate it?”

“Even if you hate it, and it’s horribly impractical, and the thing’s falling down around your ears. Even once the moment has gone, when the purpose of the thing has long since passed and you’re acting out this masque of an existence as if everything were still the same.”

And suddenly she laughs, as if hearing her own voice and the absurdity of what she is saying.

“Sometimes that’s easier?”

“Maybe so. Maybe… or it’s the thought that things might right themselves that keeps you going on. The thought that things might one day all fall back into place and everything be good again.”

“So, no plans.” Anita says.

“No plans.”

Nancy turns and walks back up the hallway to the kitchen. She pushes open the door and enters into the cool, damp greyness beyond. The smell of rain and washing detergent broods about the place. Anita follows.

“But there is one thing I’ve been meaning to do for a very long time.” Nancy says walking over to a plant pot on the window ledge. She removes a squat, dark key and unlocks the back door, “Come on,” she says, “you don’t have any other plans.”

Out, into the undergrowth behind the house. Less a garden, more a battle of branches and dripping thorny shoots. Nancy presses on ahead. Suddenly purposeful, she pushes her way through briars that loom in the sable mass of bushes. Occasionally Anita catches sight of something she recognises, a garden plant grown large and strangely wild, unchecked too long, now rampantly feral and scratching at the sky with twigs. She has no idea where they are headed, or what there could be within this growth that Nancy seems so keen to find, but she follows her, beating down the bracken, beating back the years of this woman’s neglect.

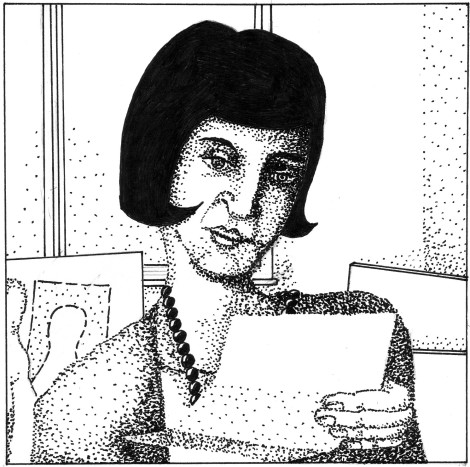

Figure XI

July 4, 2006

Up in her room she unseals it, her pulse quivering beneath her flesh. She has known that this letter would arrive, and now here it is. Beyond the unfolding of the thick A4 sheet, the unfurling of this expensive paper flower, there is only to be found quite how bad the contents are to be. She unfolds it, and there it all is:

Dear Ms. Eubank,

Following a meeting of our board of directors, it has been decided that our proposed exhibition of your work is now somewhat inappropriate. This decision was reached in light of your recent comments about The Small Gallery in the press.

Yours truly,

Henry Sitwell.

It had been such a silly thing, she thinks as she falls into the armchair upsetting two unfinished canvases onto the floor. As if in slow motion it had happened; one minute talking to friends at the private view of her friend Paul’s work, and then out of nowhere there had been this man standing at her shoulder. He was handsome, charming. She asked him what he did, but he had been somewhat vague mentioning something about the city she had thought.

He brought her a fresh glass of wine. They wandered free of the pack, discussing the exhibition. Basically it had comprised of two people’s work; Paul’s large abstract canvases of muted tonal patterns, and another man who she did not know well, who had painted these absurd figurative pieces. Strange interior scenes. Not much skill to them she had thought. The exhibition had been titled inTANDEM; a meaningless name for a meaningless exhibition. “What,” she had asked this man “are these two artists supposed to have in common? I mean, its called in tandem, but you can see who is doing all the peddling.”

The man had laughed. Anita had felt warm inside. The wine had made her witty she decided, and so she began upon a critique of the gallery’s general policy of choosing art. He laughed in all the right places; it made her feel bolder. All the time in the back of her mind she kept thinking; these people have said they will put on a show of my work… my work… no one has ever offered to do that before.

It was true. Though she knew that Paul had put in several good words for her at the gallery, and no doubt they owed him several favours during the course of staging this exhibition; nobody until then had agreed to host an exhibition of Anita Eubank’s paintings. Even though it was this funny little gallery that she didn’t much like, they were going to do this for her.

A lot of what she said to the man, he probably took out of context, but Anita could not remember much about that night the next day. It took over a month for the piece to appear in the magazine, but even after that time had passed she still recognised her words blown up as banners in the four page article: The Parochial View Of The Small Gallery. He had mentioned her by name. Why had he done that? It wasn’t as if her name carried any weight. It wasn’t even as if anyone of any importance read the magazine it was printed in. None of it mattered. But it was enough. It was more than enough.

She crumbles the letter into her fist. Paul was no longer speaking to her of course. Suddenly everyone knew who she was but for all the wrong reasons. The gallery had phoned her. It was the first she had known of the article’s existence. “We’ll be in touch by post,” was all they had said, and now here they were.

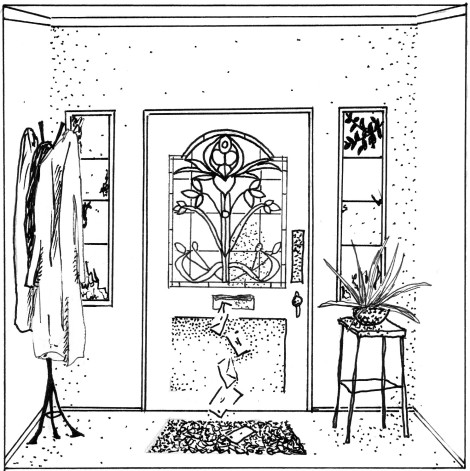

Figure X

July 3, 2006

Letters, like a windfall of poisoned apples from a tree, cascade through the slot in the front door. The house, an anomaly amid the neat town houses of Thomas Cubitt, is tucked away from the street and from the world behind a high stucco wall topped with four sandstone spheres. The postman resents the walk down the driveway. The gardener now only rarely comes, telling Nancy that there isn’t much that can be done on the amount she pays him, and if she isn’t prepared to hire someone to do the serious work then it’s a downward spiral from here on– And so the building swathes itself in the green, darkening its days as if within a wood.

Anita tentatively rises from the table and makes her way through to the hall. There it is upon the doormat, the white oblong she has waited for all week.

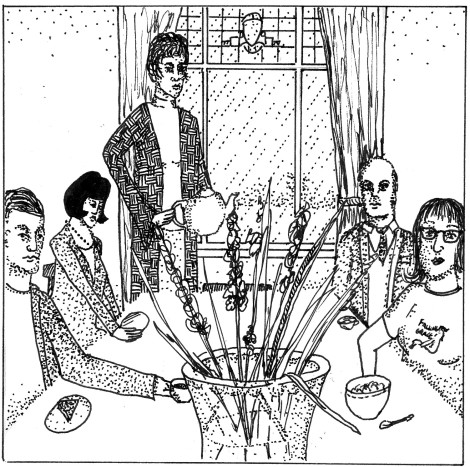

Figure VIII

June 30, 2006

Above the coffee cups and crumpets, between the chimes of the half hour, through the hazy scent of flowers cut from the garden; conversation is exchanged. Nancy brings the teapot through from the kitchen. Rupert, the salesman, describes a consignment of ladies wigs that has just arrived at the depot;

“Beautiful styles, they are Nancy, really tip-top–”

And the artist, Anita, awaits the arrival of an envelope of bad news as she has done all the week. It is through these vignettes of life that our story shall be told. Through the snatched glimpses of incident and waiting, through the momentary struggles and unimportant meals of tea and toast; all shall be documented, recorded, reported and sketched.

“And for the first time they’ve produced the Enchantment range in bruised apricot. I’ve always said that the Enchantment was deserving of bruised apricot.”

“Do any women really still wear wigs these days?” asks Laura, one of the students.

“Wigs never go out of fashion.” Rupert replies and is about to enter into his sales patter, ready to dive into the pool of familiar rhythms and rippling cadences, its proud boasts of how another look might be achieved in a matter of minutes, and these wigs are an investment – classic styles that will never look tired… when the attention of the room is taken from him by the sudden appearance of Ernest in the doorway.

Figure IV

June 25, 2006

…an artist…